Things I Read in 2023

This is a collection of the things I read in 2023 that had the most impact on me, in rough order of how much impact they had, but also divided into sections in a way that kind of ruins the order.

Pandemics

First clean water, now clean air - Fin Moorhouse

Far-UVC (light with a wavelength of 222nm) kills airborne pathogens. If we were to make all indoor lighting emit far-UVC, as well as visible light, then we might be able to sterilise indoor air, and stop the spread of respiritory illnesses. I’d already been aware of the promise of far-UVC, but this piece really brought home the parallel between this futuristic concept, and our recent past. Our cities were once ravaged by lethal gastrointestinal illnesses, but new technology, and public health programmes beat them back so succesfully that the dying of a gastrointestinal infection in a place like London or Paris is now almost unheard of. The fact that this happened makes it feel more plausible that catching a common cold could soon be similarly impluasible. We’ve done this before; it’s within our gift to do it again.

AI scaling

It Looks Like You’re Trying To Take Over The World - Gwern

A short, briliantly detailed, and terrifying story about fast takeoff.

The Scaling Hypothesis - Gwern

I didn’t realised until I’d read this that OpenAI were taking a big gamble by going big on scaling up from GPT-2 to GPT-3. At the time, most people thought going bigger than contemporary models would hit diminishing returns. But it didn’t, and… Well, you know the rest.

The Bitter Lesson - Rich Sutton

I only came across this post this year, but I think it had reached meme status long before that. It’s short and accessible too!

Absolute Unit NNs: Regression-Based MLPs for Everything - Gwern

I’m not sure I ever actually finished reading this (it’s quite long), but it uses the Vesuvius Challenge as a hook to sketch out a plan for what a really really big neural network with a very simple architecture, trained on just about all the data there is, might be able to decipher the text from a CAT scan of a pyrolised scroll, or potentially answer just about any other question you want to know the answer to.

The current AI hype cycle seems to be around architectures rather than just scaling up transformers. GPT-4 is widely rumoured to be a mixture of experts, Mixtral definitely is and it gets impressive results, and last month researchers announced a new architecture that outperforms transformers in some tests by having a (sort of, I think) unbounded context window. So in this context it’s interesting to read about an architecture that has internalised the bitter lesson. Maybe tinkering with architectures is just what ML researchers do while they’re waiting for more compute, and more data to arrive.

Fragile World Hypothesis

Brief remarks on some of my creative interests - Michael Nielsen

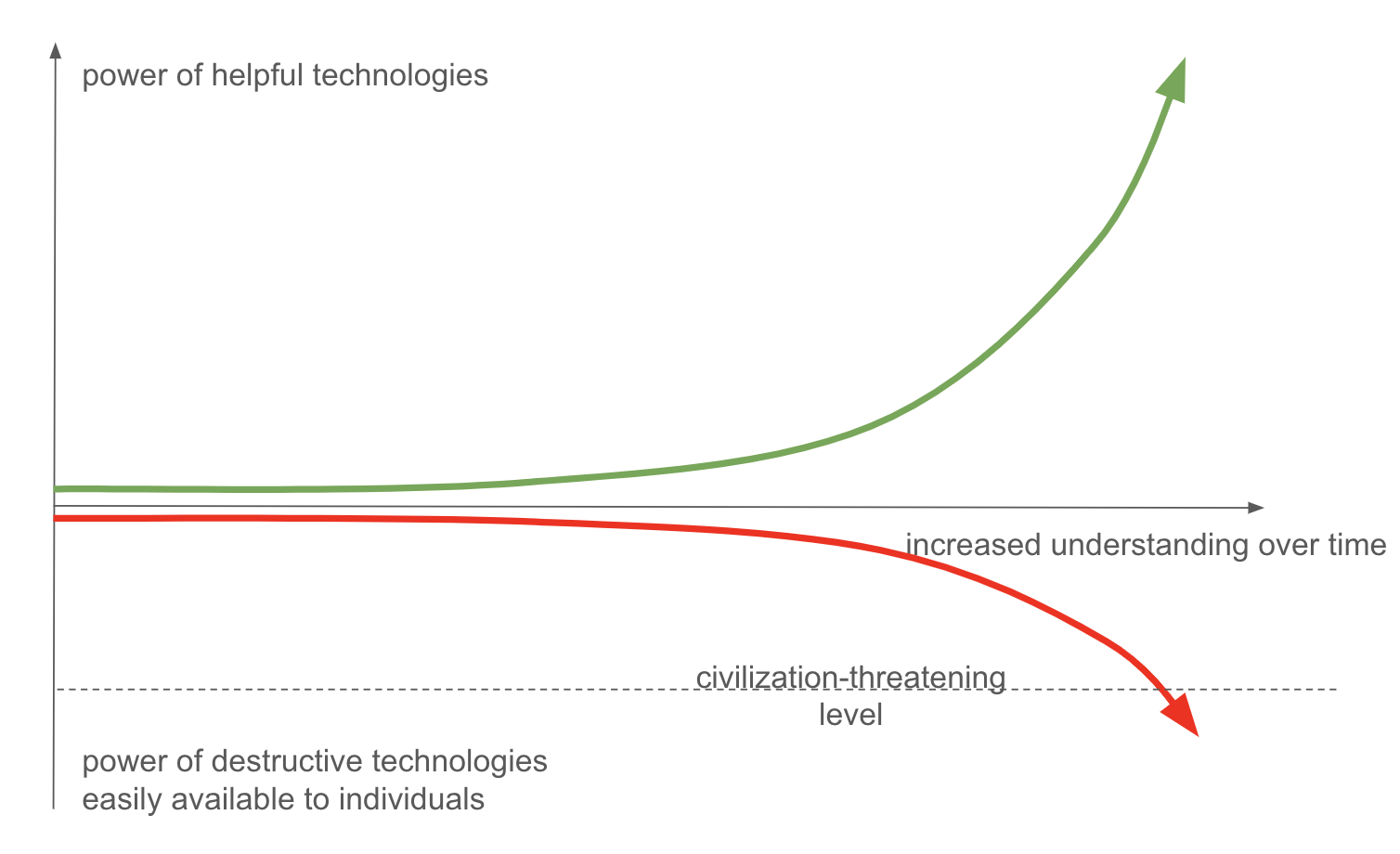

When I think of the word “erudite” Michael Nielsen’s twitter profile picture appears in my mind. He’s clever enough that he literally wrote the book on Quantum Mechanics, and yet he writes with uncommon humility. That humility is very relevant to this post, I won’t say much else about it, other than that I share his concerns, and this chart haunts my nightmares:

My techno-optimism - Vitalik Buterin

If the fragile world hypothesis is true, and there is a path that can be charted through it, then elements of that path are probably in this essay. Here’s a quote I thought was particularly good:

If someone says something that offends you, or has a lifestyle that you consider disgusting, the pain and disgust that you feel is real, and you may even find it less bad to be physically punched than to be exposed to such things. But trying to agree on what kinds of offense and disgust are socially actionable can have far more costs and dangers than simply reminding ourselves that certain kinds of weirdos and jerks are the price we pay for living in a free society.

Things Scott Alexander Wrote

Book Review: The Secret of Our Success

In 1854 the Xhosa people were in crisis. White settlers were encroaching on their land, and their cattle had started coming down with a “lung sickness”. Their response to this double threat was to make a spirited attempt to kill all of their cattle, and so as many as 400,000 head of cattle were slaughtered. Predictably, this resulted in the death, by famine, of around 40,000 Xhosa. It might seem hard to comprehend why the Xhosa would do this to themselves, but there was a reason: a 15-year-old girl in the tribe had gone to the river one day, and came back claiming to have been visited by three spirits who promised her that if the Xhosa could just kill all of their cattle—and burn their corn for good measure—the settlers would be repelled, new cattle and corn would appear, milk would become more plentiful than water, the dead would rise (in a good way, I guess), illness and age would be cured, and so on.

Prophecy may be a direct reason for the cattle killing, yet it left me with more questions than answers, as it might you. But I feel like I found some answers in The Secret of Our Success, or at least in Scott Alexander’s review of it. It turns out I was asking the wrong question. Rather than asking why a society would do this to itself, you should instead ask: why wouldn’t it? The correct answer is that it usually won’t, because destroying all of your wealth isn’t a common meme for any culture that lasts very long. But when cultural memes do change, the changes are more akin to a genetic mutation than a rational action. And so unfit memes are taken care of in the same way unfit genes are: those who would propagate them die out.

If this is true, it gives us two depressing insights: we should probably expect people to be less predisposed towards rationality than we otherwise would have, and the path towards good memes must, historically, have come at a terrible cost.

Anyway, I’ve given you no particular reason to believe what I’m saying, so go and read the review… Or the book, which I presume is good.

The Tails Coming Apart As Metaphor For Life

This essay, approaches its main topic at an oblique angle before the final reveal, as some of the really good Scott Alexander pieces tend to. If you don’t want that effect spoilt, don’t read on.

I’m unusually optimistic about life’s big questions having objective answers that can be knowable to us one day. I don’t rule out that morality could one day be quantified, and utility maximised. But this post really made that question that idea more than I usually would, and reduced my credence in it being right.

The Atomic Bomb Considered as Hungarian High School Science Fair Project

This one is spicy, and I think it’s pretty brave of Scott Alexander to write it. The spiciest part is that it’s not that easy to see why it’s wrong.

Meditations On Moloch

This was the first thing I attempted to read when I came across Slate Star Codex as something that’s a big deal. I bounced right off of it. I made a few more attempts to read it, and never quite made it to the end, but this year I did! This is really because it’s often not convenient to read articles this long, and not a reflection on how good it is, because it’s really very good. It’s another one with a long build up to a big reveal.

Construction Physics

I’m just going to list everything I read from this blog this year, because I haven’t read enough of it, and it’s brilliant.

The Story of Titanium - Brian Potter

Everyone knows the coolest metals, in reverse order of coolness are: magnesium, inconel, titanium. What I didn’t know was how difficult titanium is to work with, and how a series of US-government-funded aerospace projects pushed forward the frontier of what’s possible with it.

Why Did We Wait so Long for Wind Power? Part I - Brian Potter, Part II, Part III (Offshore Wind)

If I’d been born and raised in California I’d probably be obsessed with solar power. It’s better than wind really. But I was born and raised in the UK, so I’m obsessed with wind power, and this is a good account of it.

How the Gas Turbine Conquered the Electric Power Industry

Casey Handmer

Traffic Congestion and City Design

This is a very analytical explanation of why cars don’t work in cities. You can kind of do it if you really want to, places like LA have. But it’s ruinously expensive, everyone spends their time sitting in traffic, and it literally bulldozes every other method of transportation.

We should not let the Earth overheat! - Casey Handmer

A few years ago I thought of climate geoengineering as a last-ditch idea, that might be tried as a Hail Mary in some distant dystopian future. Now I think of it as something that will almost enivetably be done by some person or country in the near future, and this post is a sort of instruction manual for how to do that if you’re sufficiently motivated. I’m even tempted to have a go myself.

Why high speed rail hasn’t caught on

If we’re going to do air travel, the security needs to get better, and by “get better” I mean it should be less annoying. This is a bit of a defensive accelerationism idea, but really it shouldn’t be so hard to have a person and their luggage walk through a gate that scans them and has an AI declare whether they’re carrying anything threatening or not.

Architecture

Every now and then, for my whole adult life, I’ve wondered: since old fashioned architecture is almost universally adored, why can’t we build things in older styles any more? Doing so would be tacky, right? Recently I’ve started to settle that this is begging the question. We can build things in older styles, using modern materials and techniques, it’ll look nice, and no one will mind that it’s not “authentic”.

Samuel Hughes writes in favour of this view very persuasively, so I’ve included most of the essays by him that I binge read this year.

Making architecture easy - Samuel Hughes

“Easy” here means easy in the way pop music is “easier” than modern jazz. There’s nothing wrong with challenging music, because we’re not all exposed to it. But challenging architecture is obviously a different story.

Against the survival of the prettiest - Samuel Hughes

It seems like the proportion of modern buildings that are ugly is higher than the proportion of old buildings that are ugly. Surely survivorship bias explains this. We can’t have just decided to start making buildings uglier… Right?

In praise of pastiche - Samuel Hughes

Are buildings getting uglier, or are we just imagining it?

Bath Rec Counterproposal - Apollodorus Architecture

I used to live 50m away from the Rec—the home of Bath’s rugby team. It’s an eyesore. There’s a plan to replace it with a better-built, more prarctical eyesore. But some people from Bath University’s architecture department have decided to fight the good fight and put forward a counterproposal. What if, they ask, instead of rebuilding the Rec as another eyesore, we took inspiration from Bath’s ancient Roman history, took the stone for which it’s famed, took notice of our surroundings, and built something worthy of a city whose name is synonymous with old and beautiful architecture. And this was their answer:

Miscelaneous

A Protein Printer - Asimov Press AND Julian Englert

DNA printers are an off-the-shelf product now, so if you want to create a new protein, your best bet is to come up with a gene that expresses that protein, get the gene printed on a gene printer (because such things exist), splice it into the genome of some microorganism using a technique like CRISPR, you can then get the modified genome into a host organism, ferment that organism until you have lots of it, expressing lots of the protein you want, then you can finally purify that protein (somehow) to get hold of your finished product. I don’t understand any of this very well, and there are almost certainly mistakes in that explanation, but I’m very confident I’m right in saying this is a giant pain in the arse, and fails if any one of those difficult-to-pull-off steps fails.

So why not skip the fragile, and complicated middlemen, and just make proteins. That’s what this post proposes. Their method of doing so seems ingenous to me. I definitely know enough about this topic to say how good of an idea it is, I’m not convinced the authors do either, but I found it delightful regardless.

Colder Wars - Gwern

This is a very good analysis of what war in space, including interstellar war, would be like. The conclusions are almost all counterintuitive, and chilling. Space is very weird.

OpenAI: the Battle of the Board - Zvi Mowshowitz

This is sort of just gossip really, but it’s the best take I saw on what happened with the short-lived ousting of Sam Altman.

Why we need a new word for “lazy” - Julia Galef

People who don’t like working a lot roll their eyes at those that do, and accuse them of making the silly mistake of destroying their work-life balance. People work a lot accuse those who don’t of fecklessness. But maybe everyone should just… Chill out a bit. It’s easy to say, but the hard-working people really have a leg up on hoovering up resources and making the world in their image. Still, this post is great, and I endorse its message.

Two Types of People - Robin Hanson

This is an interesting lens through which to view people. I won’t spoil what the two types of people are, but the theory seems plausible to me. Even if it’s not correct, it might still be a useful analogy.

This is the Dream Time - Robin Hanson

We just live at a very strange time in cosmological history. So strange that we should almost be suspicious of it… Anyway this does a good job of capturing some of that strangeness.

The Energy Kite - Makani Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

I got obsessed with airborne wind turbines this year. Makani came the closest of any company to realising the AWT dream, but eventually folded, and—nobly—released a very detailed report on their progress, challenges, and now-defunct future plans. This is more in the weeds than anything else on this list, and I’ve not yet made it to the end, but I think I was able to learn from it even as someone with very little knowledge of aeronautics.